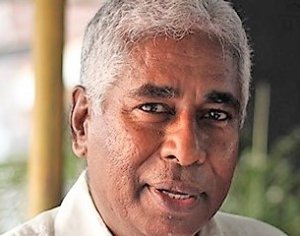

Remembering Teacher

We had thronged into an afternoon English lecture in the University College, Trivandrum.

The year was 1969 and we had just joined the graduate class. What is left now are not

memories but vague and discrete images. English was a difficult subject for most of us; it

remained as opaque as a block of lead for many. And those who found it light going chose to

attend as few classes as possible. We hadn’t waited for more than a few minutes when

Hrdayakuamari teacher briskly walked in, looked around and sat down. She was dressed, as

always in well ironed khadi saree, white or off-white.

She then wrote on the blackboard in big capitals, ‘NOVEL’. That made us more attentive,

listening to a story is worth the effort even on a late noon hour. She turned around and said

she would be handling Thomas Hardy’s ‘the Return of the Native’, the novel prescribed for

us for a nondetailed study. She didn’t elaborate on the novel, nor did she give the abstract

of it. Instead she asked us a plain question, ‘what is a novel?’ Though we all thought we

knew what a novel looks like, when we began to discuss its basics, oh, we are stuck. What

makes the Pickwick Papers a novel but not Saki’s work? Why do you call Dracula and the

little book ‘Old Man and the Sea’ novels?

Hrdayakumari teacher (we used to address ladies as teachers; the word ‘madam’ was yet to

be invented for teachers outside the medical colleges) never lectured on the plot, she

considered issues that made the characters do what they did and suffer what they suffered

that gave meaning to the novel. I found the classes so illuminating that I sat and read the

novel over the next couple of weeks, though Hardy was hardly read those days. I got

interested in literature generally and went on to tackle Shakespeare (Macbeth, in my time)

with passion.

It’s not only in classes that I met teacher. She used to conduct a weekly after-college-hour

discussion session with students. The hour was spent on discussing contemporary issues

from an academic point of view, structured and relevant. Teacher herself did not talk much

except to intercede at critical points. This was a fine tool; it helped us to think, speak and

listen: I didn’t do any speaking, I was a silent listener. The group was always small, there was

one woman (whose name I cannot recall) student who came from the Women’s College.

There was Arun who later on was part of the Obama administration, Rasheed who is a

distinguished professor at Texas and Rajan a busy chartered accountant. The other faces

have departed my memory software. At some point I dropped out, finding perhaps that I

had nothing to contribute!

I had another occasion to meet her. In 1967 she taught English in the Intermediate College,

Trivandrum. My seniors used to say, there goes Hrdayakumari teacher, as she walked on

the passageway of the first floor of the college. For me, she was the first identified face of

teachers. I was not in one of her classes, but from what I learned from others, she was the

best teacher of English. She was in charge of the rhetoric club; when the club was

constituted, I went there to try my luck at gaining entry to it. The test was a passage from a

book which all hopefuls had to read. Of course, I didn’t qualify.

Later on I had other occasions to listen to her. She was one of the few intellectuals who

could use English and Malayalam with equal prowess, shift seamlessly from one to another.

She could observe trifles and details in everything around her; perhaps that is what

romanticism is all about. Her book, ‘Kalpanikatha’ studied Asan, Edapally and

Changambuzha on the way romanticism blossomed in them. Meanwhile, there are very few

serious works on Edapally.

Remembering Hrdayakumari teacher is an act of worship.