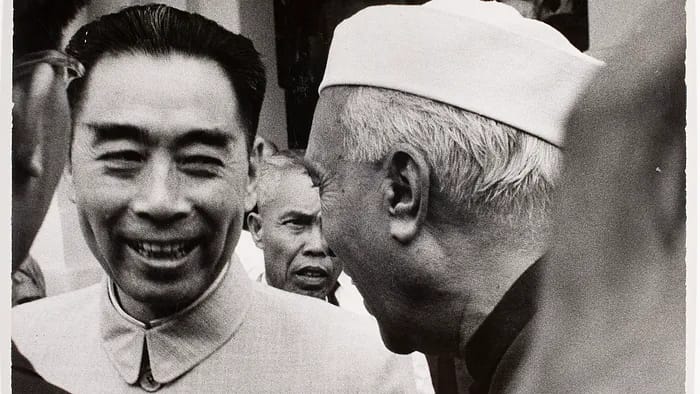

The Second “Panchsheel”

Jawaharlal Nehru & Zhou Enlai, architects of the first Panchsheel|Photo credit: Lisa Larsen, International Center of Photography

In 1954, India and China signed an agreement in which the two sides emphasised that the Five Principles (“Panchsheel”) of mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other's internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence, would ensure peace and stability in Asia.

But what followed was a period of conflict, war and tension on the border, which necessitated many agreements to deal with specific situations.

Now we have another “Panchsheel” signed in Moscow by External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and Foreign Minister Wang Yi on 20 September 2020, but it is still not clear whether it will lead to dialogue, disengagement and distancing, considering the distrust between the two countries and the deep Chinese conspiracy which created the incendiary situation along the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

But there is reason to believe that India’s three-pronged strategy of dialogue, military preparation and economic action has halted the Chinese adventurism for the time being.

The roaring of the Rafael jets, the Indian occupation of a few commanding heights on the Southern Bank of the Pangong Tso, setting up of the barbed wire “Lakshman Rekha” and the deployment of the Tibetan forces may well have prompted the Chinese to grasp “the last chance for a peaceful resolution,” as they called the Moscow meeting.

Disengagement was promised before, but what followed was a period of casualties on both sides, tension and some proactive movements of troops from India. The second “Panchsheel” is no guarantee of implementation, and it may have a shorter shelf life than the first one. A record of the “frank and constructive discussion” in Moscow with the apparent blessings of Russia and Iran has a chance of implementation, though the text has the potential to be interpreted in different ways.

Significantly, Wuhan and Mamallapuram made an appearance in Moscow at a time when it appeared that they were thrown to the winds by the Chinese when they planned the incursions. PM Modi and President Xi had appeared to be engrossed in each other and no one believed that those conversations would be in vain. PM Modi was accused of misreading Xi even after fifteen meetings with him.

We do not know the nature of the “consensus” reached between the leaders, but certainly the reset was not to have a bash at each other on the border. India gave some concessions to China in the wake of the Wuhan spirit, but there was no sign of reciprocity from the Chinese side.

To say that “the current situation in the border areas is not in the interest of either side” is to acknowledge the obvious. It is logical, therefore, to continue the dialogue, quickly disengage and maintain proper distance, as the pandemic has taught us, to avert danger.

The word “disengagement” is crucial as the Chinese believe that they have disengaged enough and it is India which has to disengage from the Chushul area. This determination is as hard as determining the border and the process may go on till the winter and beyond, leaving the situation favourable to the Chinese, who may not have intended to achieve more.

We have acquired a few bargaining chips by our action in Chushul, but the Chinese have many more of them along the LAC and that explains their reluctance to agree to restoration of the status quo.

The consensus to abide by all the agreements, including the agreement of 1993 to maintain peace and tranquillity is mandatory and logical, but China is a habitual violator of this obligation and the way it has been written this time is simply a reminder of the violations that have taken place. Agreements are meant to be followed and not to be flouted.

The agreement to continue the dialogue through the mechanism of the Special Representatives and the Working Mechanism for consultation and coordination is welcome, but without a commitment to move to a time bound programme to conclude these consultations, such an agreement is redundant. The Chinese seem to consider the negotiations on the border endless till they have sorted out the LAC to their complete satisfaction. Such a dual path is fraught with dangers as the process of sorting out of the LAC is pure banditry and lawlessness.

The Joint Statement ends with a call to conclude new and undefined Confidence Building Measures, making enhancement of peace and tranquillity in the “border areas” not LAC, conditional to the CBMs. This amounts to a rewriting of the agreement of 1993 and makes violations legitimate in the meantime.

It was feared that the Moscow meeting would end in a fiasco in which China would give an ultimatum to India to withdraw from Chushul and India would insist on restoration of the status quo as in April 2020, leading to a conflict situation.

The Joint Statement has averted such a disaster for the time being. When India is battling Covid-19 and the looming economic crisis, any respite is welcome and China itself is facing serious international hostility for flexing its muscles in multiple areas.

At best, the Moscow consensus is a breather for the two countries only to be tested in the process of implementation.

China has not given any explanation for its initial moves, though the changes in Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh have been cited as a possible provocation.

Such a reason, if raised, would be disastrous for India-China relations in the long run. The present consensus makes it possible to veer away from such a fundamental position and to stay close to the delineation of the border as the core issue.

Scepticism is the prevalent mood in the country and the Joint Statement has many elements in it to make anyone sceptical. But the effort made to define the larger picture by focussing on history and the wish not to turn differences into disputes and conflicts is welcome.

In the obtaining circumstances today, nothing more could have been possible. At least the vicious circle of Chinese incursion, discussion and partial withdrawal has been broken and attention has turned to long term solutions rather than short term gains.

Surprisingly, the Defence Minister referred to the Moscow agreement at a low key in the Lok Sabha on September 15. After stating that he had clearly told the Chinese side that any unilateral attempt to change the LAC would be strongly resisted, he said: “My colleague, Shri Jai Shankar, the External Affairs Minister, has thereafter met the Chinese Foreign Minister in Moscow on 10th September. The two have reached an agreement that, if implemented sincerely and faithfully by the Chinese side, could lead to complete disengagement and restoration of peace and tranquillity in the border areas.” This obviously means that India does not consider the Moscow agreement a breakthrough, not even a temporary reprieve.

The million dollar question is what China’s next move would be. Would they be content with holding on to Galwan valley till the snow melts next year, leaving India to hold the heights it has taken? If not, what will save the face of President Xi? If he considers it a setback, heads will roll in CPC and PLA. Further, if he needs a personal victory, he could force further conflict in Ladakh.

In that conflict, the Chinese, Richard Fisher of the Virginia-based International Assessment and Strategy Center tells Gordon Chang of Newsweek, could roll out "joint mechanized warfare for which they have been preparing for 30 years.”

But victory is not guaranteed after the smart moves of India this time. “Unfortunately, it looks like China's leader, who had looked invincible, now has something to prove. As a result, he appears absolutely determined to make his point by launching another attempt to break India apart,” says Gordon Chang.

If the first Panchsheel did not prevent 1962, there is no guarantee that the second Panchsheel will prevent a repeat in 2020.

As far as India is concerned, a return to the situation in April this year will be victory.