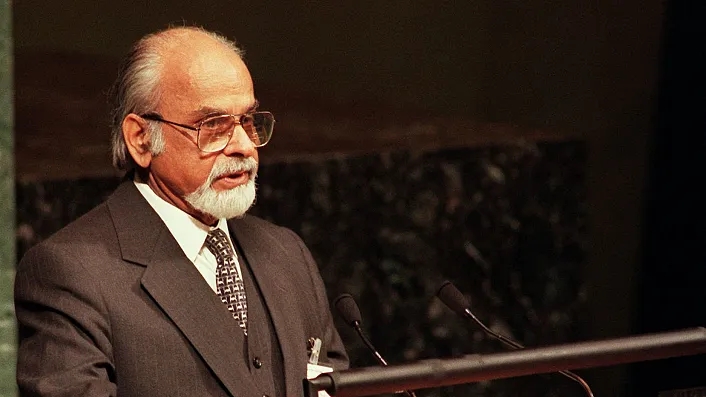

Centenary Thoughts on Inder Gujral, the Gentleman PM

The elevation of Inder Kumar Gujral as Prime Minister appeared to be the outcome of a chaotic political situation which led to the unexpected emergence of Deve Gowda and Gujral as Prime Ministers for relatively short periods. But anyone who has followed the political career of Gujral will see some poetic justice in his Prime Ministership. He had the qualifications, experience, wisdom and discretion, even though his rise was not expected to this extent.

Gujral joined politics as a Communist in his youth, after having been in jail as a freedom fighter with his father, then joined the Congress Party and became a member of Indira Gandhi’s “Kitchen Cabinet,” then left the Cabinet to become the Ambassador to the Soviet Union during the terms of three Prime Ministers, served as Minister of External Affairs with two Prime Ministers and finally became Prime Minister. Moreover, he performed well in every position he occupied, regardless of the circumstances which placed him there.

We had expected that Gujral would arrive in Moscow as a disgruntled Minister who was abruptly sent away as Ambassador. But the two years I worked with him in Moscow, I found him working incessantly and enthusiastically to learn the art of diplomacy and to improve India-USSR relations. He brought in revolutionary changes in the upkeep of the Embassy and its contacts with the host Government. Flowers began to bloom in the garden and the abandoned Napoleon’s dacha was restored and the Embassy’s squash court was opened to other diplomats.

Though left -of- centre ideologically, he had aristocratic tastes, which helped his transformation as a diplomat and brought elegance and style to the Embassy in Moscow at some cost to the Government. The efforts made by the Ministry, particularly Additional Secretary S.K.Singh to impose financial discipline on him ended up in a tussle which cost S.K.Singh part of his term as Foreign Secretary when Gujral became the External Affairs Minister.

Gujral was an avid admirer of the Soviet Union and was convinced that the Soviet Union was on a trajectory for exceptional growth. Once he sent a crash message to Y.B.Chavan, who was the EAM at that time to say that the 21st century belonged to the Soviet Union. Having been woken up to receive the message, Chavan wrote to him that the message could be sent the next day as the 21st century was still some time away!

Gujral took interest in all aspects of Indo-Soviet relations, particularly the economic and cultural spheres. He put together a team of his own choice and followed a collegial approach. He would listen to everyone, but once he made up his mind, he would stick to his position and implement his decisions. He rarely raised his voice or show impatience. Having caught between him and the Ministry on administrative matters, I was often slow in delivery, but he reminded each time as though it was the first reminder. The onus was on me to get the work done.

It was after a visit to Sochi that Gujral returned with a beard that stayed with him for the rest of his life. I asked him about it at the airport. He replied that a female hair stylist in Sochi discovered how much like Lenin he would look if only he had a beard. He accepted her suggestion that it would be great for an Ambassador in Moscow to look like Lenin.

He was basically opposed to the Emergency rule, but he never revealed to us or the Soviets that he was not fully with the Government. It was only after the formation of the Janata Government that he began sharing his reservations with us. He agreed to stay on as Ambassador under Prime Minister Morarji Desai and made a difficult transition for the Soviets as smooth as possible. When Foreign Minister Gromyko went to meet the new leadership in India, he remarked that the presence of Gujral at the talks gave him a sense of comfort. The visit of Morarji Desai to the Soviet Union presented many challenges because of “genuine non-alignment”, but it was Gujral who applied the soothing touch. Morarji’s insistence that no reference should be made to the Indo-Soviet Treaty held up the Joint Statement till the last minute, when Gujral intervened. Foreign Secretary Jagat Mehta, Ambassador Aravind Deo and I had given up any hope of a compromise.

It was his performance in Moscow that led to his appointment as the EAM, but he found his new charge formidable. He was accused of cronyism as he involved his old friends and associates in formulating policy at a time when the PMO was not very dominant in foreign policy. His worst moment was the time of the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait. Having been advised by our envoys in the Gulf that the change was permanent and our priority should be to evacuate Indians as soon as possible, Gujral visited Baghdad, embraced Saddam Hussein to the horror of the international community and brought back some Indians in his own plane to India. Though the evacuation went smoothly, the visit disappointed the GCC countries and they held Gujral responsible for encouraging Saddam’s aggression. India became suspect in the eyes of those who fought the first Gulf War. Several Gulf countries avoided meeting him at the UN General Assembly session.

What came to be known as the “Gujral Doctrine” was essentially a thesis that strict reciprocity should not be demanded from our smaller neighbours so that they feel comfortable to build partnerships with India. It also meant that the small neighbours should not act against India’s interests and should not interfere in each other’s internal affairs. The ready withdrawal of the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lanka at the request of Sri Lanka was one example of the Gujral Doctrine. While the countries concerned welcomed the Doctrine, they saw it as a sign of weakness in the face of growing Chinese influence in the region. It is to Gujral’s credit that he never promoted it as a doctrine, but as a practical way of promoting goodwill in the neighbourhood. He was quite capable of taking tough decisions, once he was convinced about a particular issue. The way he rejected the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) was a case in point.

As the head of a motley group of parties with Congress support from outside, Gujral is not credited with any major achievement during his short tenure as Prime Minister. Internal problems plagued him till the very end. But he focused on relations with Pakistan and the United States. He had a cordial relationship with Nawaz Sharif, but terrorism loomed large and there could be no meeting point. But he told me once that he got Nawaz Sharif to agree that neither India could give away Kashmir to Pakistan nor Pakistan could take it under any circumstances as the bottom line.

Gujral personally ordered my posting to Washington as the Deputy Chief of Mission in 1997 when it appeared that President Bill Clinton might visit India in early 1998. He had met Clinton in New York, leading to some criticism that he readjusted his schedule to be in New York when Clinton and Nawaz Sharif were also there. He was accused of falling into a trap set by the Americans to mediate between India and Pakistan. He told me during a briefing on the eve of my departure to Washington that there was no trap of any kind and Clinton was very sincere about normalization of India-Pakistan relations. He was very particular that the visit should take place even after he became a caretaker Prime Minister, but the Americans decided to wait for the elections and the rest is history. Americans were generally positive about Gujral and the point man for India in the State Department, Rick Inderfurth, was so friendly with Gujral that a cartoon appeared in which a son was asking his father, “Are Inderfurth and Inder Gujral brothers?” Inderfurth asked Gujral to sign a copy of the cartoon and he did so with the comment, “Who knows?”

Gujral’s most admirable quality was his personal warmth to his colleagues, regardless of the position he held. He commanded loyalty from everyone who worked with him and helped them in return. When he was in Delhi and I was abroad, he was like a local guardian for me to whom I could approach for fixing things like school admissions, ration cards and housing. When he became the External Affairs Minister and Prime minister, I stopped asking him for such favours, but he asked me every time we met as to whether I needed anything. He decided on his own that I should go to Washington despite bureaucratic objection that I had already served in the US twice before and created history by the PM himself appointing a Deputy Chief of Mission!

In a Foreword for my first book, ‘Words. Words, Words: Adventures in Diplomacy, he wrote: “I have heard Sreeni addressing UN meetings, seminars and conferences. He always has something to say and he says it convincingly, effectively and with a sense of humour. I have received good advice on foreign policy from him during my days as Ambassador to Moscow and as Minister of External Affairs and as Prime Minister.” Such was his graciousness and generosity to those who worked with him. No wonder he is remembered as the “Gentleman Prime Minister” in his centenary yea